http://world.honda.com/history/challeng ... xt/05.html

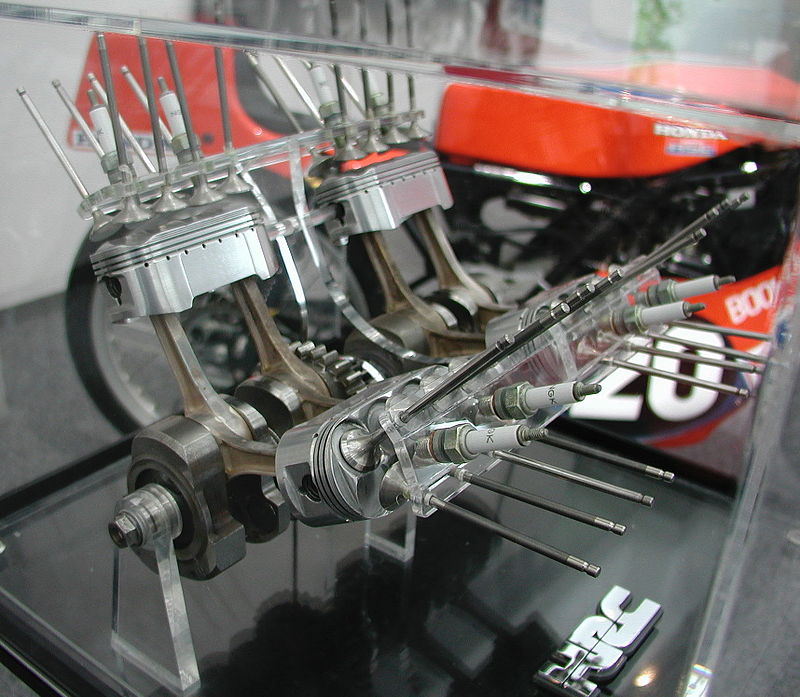

Key problems in the team's engine design included the gear train and valve system. In the former, a reduction gear was initially used to turn the cam at half the rate of crank revolution. However, since it had been a source of frequent failures, a normal cam-reduction gear train system was adopted. Still, the problem refused to disappear. Numerous options were tried, after which the team came up with the idea of a rubber damper that would mesh with the cam gear. Fortunately, the design was a success, allowing the valve system to turn properly. Moreover, it resulted in higher power output.

Additional areas of concern were the over-effectiveness of engine braking and a sudden burst of power when the throttle was opened (the so-called "bang"). The problem of engine braking was quickly resolved through the use of a device called a "back-torque limiter." However, the team couldn't find an absolute solution for the "bang."

The NR500 improved slowly but steadily, thanks to the team's dedicated effort. In 1982, their 2X modified engine achieved 135 horsepower, and in 1983, a 3X unit demonstrated output of 130 horsepower. The oval piston engines were at last on par with their rivals, at least in terms of output.

Despite their enhanced output, the performance of Honda's engines was not so impressive on the track. Even though the Honda team earned a victory in the 1981 Suzuka 500-Kilometer Race using an oval piston engine, that was to remain their only triumph. The World Grand Prix series was an ongoing struggle.

Weight was a major handicap. Since the four-stroke engine required a larger cylinder head, its weight was greater by around 20 kg. The added mass surrounding the head also affected the machine's center of gravity and overall balance. Measures were taken in order to reduce weight, including the replacement of iron with titanium and aluminum-already a light material-with magnesium. However, the precious improvement gained was quickly lost, as Honda's rivals began using the same approach.

Other measures were taken to save weight. These included a reduction in the thickness of the outer crankshaft, which was subject to a relatively minor dynamic load. Often, before a race, the staff would labor overnight, grinding the parts with a pencil grinder. Still they were unable to overcome the weight disadvantage. It was a problem that would not be completely solved until a successor to the NR500 could be built.

Three years had passed since Honda's highly anticipated return to the World Grand Prix series, but the NR500s had yet to win a race on the international circuit. Still, no losing streak could last forever, and Honda knew it. There was increasing pressure, both in Japan and elsewhere, for Honda to take the checkered flag.

As a compromise in the effort to get on the winners" podium, in 1982 GP series Honda introduced NS500 machines powered by two-stroke engines. The NS machines gradually replaced the NRs and, with that, came to play a dominant role on the world stage of motorcycle racing.

The 3X engine was developed in 1983 as the last of the (oval piston) competition series. The 3X certainly had sufficient potential to win the World GP race, with an impressive 130-hp/19,500-rpm output. However, the remarkable results of the NS500 machines kept the 3X machines on the sidelines, shelved away in the pits. Finally, Honda decided to take the 3X off its roster of race machines without ever giving the engine a chance of competing.

"Although it couldn't win a race," said Yoshimura, "the 3X was very close to the complete form of an oval-piston engine, achieving more than 95-percent maturity."

The development staff could, after all, achieve the engineering target it had set at the beginning. The experience, however, had left them with a deep sense of frustration.

"The engine was designed for racing," Yoshimura said, "so we wanted it to be a winning design. If we had won at Laguna Seca, we could have been content with that and put a more peaceful end to the engine's racing history."

In reference to that, the engine did indeed have a chance of winning at Laguna Seca in July 1981. It was not a World Grand Prix race, but it was nevertheless an important event. During the race Freddy Spencer, riding his 2X, led Yamaha's Kenny Roberts for quite some time. Although Spencer ultimately retired with an electrical problem, it was a race that amply demonstrated the 2X engine's potential. Spencer's brief but powerful domination had assured the development staff of the NR500's potential, and despite all the hardships it was a lasting reminder of their effort and its ultimate value.

The NR500 concept was succeeded by the NR750, a commercial bike released in 1992. In fact, the back-torque limiter and other technologies evolving from the NR500 development saw their way into many mass-production Honda machines. The most precious outcome of the experience, though, was the spirit of challenge that was kindled by the original development staff and passed on to a new generation.

Reminders of the many trials involved in NR500 development have found a place in the hearts and memories of everyone involved. Until recently, in fact, a drawer in Yoshimura's desk contained damaged connecting rods and broken valves, which came from assemblies that fell apart during early bench tests.

"Every time I saw those parts," Yoshimura recalled, "they reminded me of the enthusiasm we had during development. They reminded me of a hotel in Nasu in the dead of winter, where we wrapped ourselves in blankets as we drew layouts because the heater wasn't working. I remember our excitement at finally having completed the drawings. Of course, they also brought back bitter memories from those races."

From its comeback in World Grand Prix with four-stroke engines to the creation of oval piston engines, Honda continued setting high goals and fostering the spirit of challenge in every aspect of development. The wealth of new technologies now possessed by the company is in no small part a result of these efforts.

"To create anything, you must put your heart and soul to it," said Yoshimura, in nostalgic reflection on those days. "The development of oval piston engines impressed that upon me, as well as on the other young engineers."

The parts are now gone from Yoshimura's desk drawer. They were given to young development staff for use as reference materials in future endeavors. Yet, those parts are pieces of a dream that Yoshimura hopes will grow in the hearts of his successors and again drive them to new innovations.